You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Reviews’ category.

Don Thompson’s re-imagining of the Jules Verne Classic is reviewed by the festival, where it won an award.

“The script is engaging and very well written, and would be perfectly suited to become a series of films…” — Hollywood Gold Awards

You can read the review here.

“They were like butterflies, it was like they never slept,” said Mr. Vounta, recalling the bombs that the U.S. dropped on Laos from 1964 to 1973. Mr. Vounta is one of the voices featured in This Little Land of Mines, a film by Erin McGoff, a 2017 Student Fellow from American University. The film premiered at the Landmark Bethesda Row Theater on Thursday, July 18, 2019, to an audience of nearly 200 that filled the theater.

Read more here.

Erin McGoff at the Q@A for ‘This Little Land of Mines’ World Premiere on July 18th, 2019.

Erin McGoff at the Q@A for ‘This Little Land of Mines’ World Premiere on July 18th, 2019.

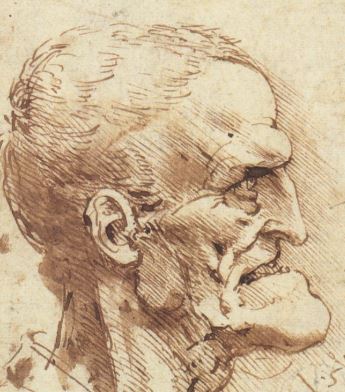

I just finished the audio book by Walter Isaacson about the life of Leonardo da Vinci. I would highly recommend it to all as it conveys a sense of not only the man, but also what a life devoted to creativity can be.

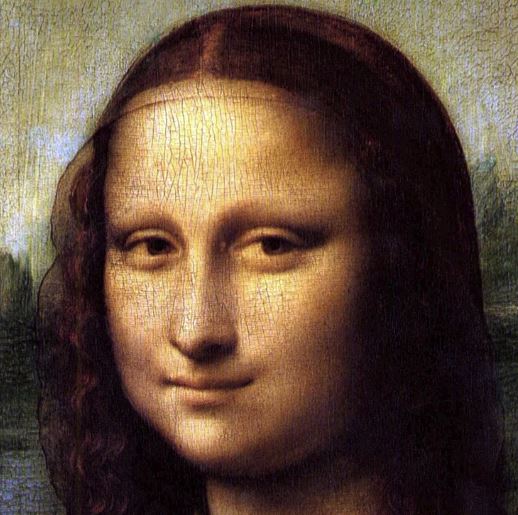

And what is that? Interestingly, it is the liberal spirit of experimentation and willingness to fail, or half complete works, that was the hallmark of Leonardo. For example, he only completed four portraits of women – one of which is considered by many to be the best Renaissance painting and emblematic of the time – the Mona Lisa. Many of his projects, and paintings, were left unfinished.

Another interesting and inspiring aspect of Leonardo was his willingness to invent technique and his success at doing so. Among those techniques was Sfumato – the  technique of intentionally blurring lines and color to create an overall sense of realism. How? Because in life there are no ‘lines’, there is only the interplay between light and dark. The two often blend harmoniously.

technique of intentionally blurring lines and color to create an overall sense of realism. How? Because in life there are no ‘lines’, there is only the interplay between light and dark. The two often blend harmoniously.

Leonardo never wrote an overarching treatise – there is no opus book or books that depict his philosophy or conveys his style. Rather, he kept thousands of pages of notes, all that were apparently designed to inform himself and remind himself of certain aspects of whatever craft or art he was trying to master, including the craft of designing buildings and machines of all sorts, some of them machines of war.

He was, then, a blend of artist and scientist, and investigator into the known and unknown, who chronicled what he observed for sometimes mundane, sometimes profound reasons.

A bit more about sfumato. For me, sfumato not only revealed a style, but a perspective on life. In sum, life is not absolute light and dark, good and evil. It is, rather, the  constant shades between. So sfumato as a technique is inherently humanizing. It emphasizes that nothing is perfect: there are no straight lines, there is no definitive light and dark, and there certainly is no perfected human form. By inference, there is no perfect human being.

constant shades between. So sfumato as a technique is inherently humanizing. It emphasizes that nothing is perfect: there are no straight lines, there is no definitive light and dark, and there certainly is no perfected human form. By inference, there is no perfect human being.

What the technique of sfumato allows to happen is for the innate human inner light to shine through: a light that points to another kind of perfection. That is, that the light is imperceptible in a sense, and yet, perceived on some level as the human spirit. Often, but not always, that spirit is compassionate. Other times it is cruel. At yet other times, mysterious. The genius of Leonardo was his ability to convey that spirit and light in all its forms.

This does not at all mean we should stop attempting to be better human beings or to shape our own moral code. Rather, it prompts us to have a broader, hopefully wiser perspective. In other words, the passion for truth and beauty does lead, it seems to me, to an understanding that no one has an absolute claim on it. It is, rather, a sfumato. It is a blurring. It is in this blurring that we can find our common humanity and can abide peacefully in the light that pervades all of experience. This ‘great light’ is not so much a ‘spiritual’ light only for the religious – for a artist like da Vinci perceived it without necessarily always being overtly religious. It is the light of sfumato.

You can find a link to the amazon page for Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonardo here.

Don Thompson is a producer, filmmaker and playwright.

Seeing director Sean Baker’s The Florida Project reminded me quite unabashedly that there is more than one way to tackle the art and craft of filmmaking. In the United States, because filmmaking is so rooted to this day in story telling techniques that can be traced back to the so-called ‘Hollywood style’, The Florida Project will certainly make  some people squirm in their seats because they are not delivered the well-defined story memes heaped up from Hollywood directors like so many pre-packaged and colorful Gummy Bears the viewer might be inclined to purchase prior to entering the theater.

some people squirm in their seats because they are not delivered the well-defined story memes heaped up from Hollywood directors like so many pre-packaged and colorful Gummy Bears the viewer might be inclined to purchase prior to entering the theater.

As far as mainstream movies are concerned, Hollywood is generally more worried about box office than art. In seeming rebellion, The Florida Project reminds me of an alternative universe of storytellers that countered the Hollywood style in the 50’s and 60’s, including but not limited to European directors such as Francois Truffaut, Michelangelo Antonioni, Vittoria De Sica, and others. And in that mix we must also include Asian directors such as Ozu.

These similarities take their shape in terms of both the way the film is shot and edited, as well as its content. The Florida Project was shot and edited in a distinctly non-American style, and its content focuses on the shadow world of poverty that many Americans would prefer to ignore.

In terms of how the film is shot, I was immediately struck by the emphasis on what can only be termed mise-en-scene – literally, the use of the frame and the compositional elements displayed to make a statement, usually using a static, wide shot. The constant wide shots of the film’s child characters marching past Floridian architectural oddities shows the indelible influence of environment and context on the children. It forces us into the moment, rather than moving us kinetically into the next scene via relentless editing.

Mise-en-scene, as such, is a political statement. It tells the viewer that the director wants you to linger on the scene and reflect on it, rather than move on to the next item in the shot list and not think about what you’re seeing too much. A master at this technique was the Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu.

Ozu’s Cinematography (from the review of Early Spring)

Ozu’s mise-en-scene was famously different from most other filmmakers across the globe, although his style has directly influenced some filmmakers, such as Hou Hsiao-Hsien. His camera is almost invariably set at a low angle, as if from a low sitting position and looking up at the characters. The image compositions are static, and there is almost no camera movement. Even when the camera tracks horizontally, it maintains a fixed composition on the principal characters of the shot. Thus the camera seems to be rooted to the environment, and pays little attention to the eye-line axes of the characters.

It is precisely this effect of ‘rooted in the environment’ that Sean Baker explores with The Florida Project. The use of mise-en-scene, combined with the fact that the film is virtually without music, certainly displays one of the most rebellious directorial styles seen in the United States recently, certainly since Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life – a film that also showed a lot of European influence, including most predominantly the emphasis on architecture (also found in The Florida Project) so prevalent in the films of Michelangelo Antonioni. You can read my review of The Tree of Life here.

That said, Mr. Baker is not quite as serious in intent as Malick, and does seem to want to make audiences happy, and does so with a technique often employed by Francois Truffaut (for example in The 400 Blows) and Vittorio De Sica (in Bicycle Thief) – that is, the prevalence of cute. And even beyond cute, The Florida Project displays a Christ-like innocence that evokes pity.

Cuteness, innocence and pity are the elixir that binds the viewer to the screen with The Florida Project where they might otherwise turn away. A similar tactic was used in the film Little Miss Sunshine, but that film had a much more conventional shooting style than The Florida Project, and was also more cynical in its conclusions about human nature. The primary purveyor of this innocence is The Florida Project is the central child character, Moonee, as played by Brooklynn Prince. Moonee, if taken as a symbol, is the lunar child, the mysterious nature that pervades The Florida Project and would certainly overwhelm the machinations of suburban bliss laid out by mankind should we ever die off of from a plague or other calamity. Moonee’s mother, played with effervescent verve by newcomer Bria Vinaite, is also fundamentally innocent – a passionate activist for her child’s wellbeing – as much a product of an unfair system as anything to do with her own failings.

It is no accident, therefore, that the children want to burn down the house in the cookie cutter suburb that has turned into a dilapidated wasteland. Moonee and her friends, in burning down the house, show that they are in alignment with nature, not with the supposed security of the corporate human as displayed by the ‘normal’ people who swamp into Disney World – a manufactured realm of make-believe that the children of the welfare hotels cannot afford and must therefore turn constantly to their own imaginations to replace. And yet, their ‘crime’ is imbued with innocence – no one is hurt, and perhaps if all the abandoned homes were burned down, nature could more effectively reclaim its rightful status.

The father figure of the film is the ever-present motel manager, played by Willem Dafoe. Dafoe’s character introduces us to the implications of human choice that Mr. Baker  wishes us to contemplate. While the environment and context in The Florida Project may be quite cold, and the omniscient helicopter ‘observer’ of the entire human enterprise that drones endlessly in the background quite detached and empty, human choice is nonetheless a key factor in introducing compassion into the equation. The manager, then, is closer to God than is the environment and nature, which again is shown to be irrevocably detached. God – should he or she be presumed to exist – emerges from nature as a human construct. The film compels us to conclude that human beings can create good where it otherwise might not exist.

wishes us to contemplate. While the environment and context in The Florida Project may be quite cold, and the omniscient helicopter ‘observer’ of the entire human enterprise that drones endlessly in the background quite detached and empty, human choice is nonetheless a key factor in introducing compassion into the equation. The manager, then, is closer to God than is the environment and nature, which again is shown to be irrevocably detached. God – should he or she be presumed to exist – emerges from nature as a human construct. The film compels us to conclude that human beings can create good where it otherwise might not exist.

At the end of the film, Moonee’s friend takes her on an excursion back to American normalcy, which to the poor children of the welfare hotel is the fantasy of Disney World and Cinderella’s Castle – the proverbial destination for all young American girls. The fact that the girls never really reach the Castle is, it seems to me, intended – for it is the idea of the Castle, not so much the Castle itself, that eggs the girls on to their destination. It is the promise of the thing – not the thing itself – that motivates human beings. Seen in a larger context, it is the promise of hope and freedom that elevates people — that no matter how illogical and silly it may seem to cynics, hope is nonetheless a powerful motivator for the supposedly naïve people of the world who still need to believe in something.

For without hope, human beings cannot be said to be fully human. The Florida Project shows us how this truth still resides with us as much as it did a half century ago, or indeed a millennium ago, or even perhaps when human beings first looked out from  over a hilltop, and saw the Promised Land beyond.

over a hilltop, and saw the Promised Land beyond.

Don Thompson is a producer, filmmaker and playwright.

What’s interesting in writing about films that attempt to move the medium forward is that such films tend to impact the mind of the critic a little bit more than others. They begin a thought process where one idea inevitably leads to another in an interesting, intuitive but generally causal way. Such it is with The Shape of Water, written by Guillermo del Toro and Vanessa Taylor and directed by Mr. del Toro.

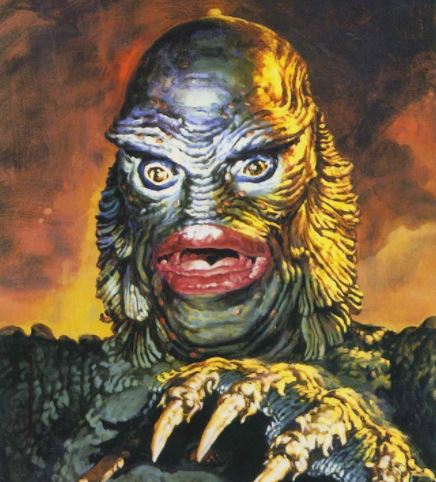

I admittedly lack an in-depth knowledge of del Toro’s previous work – most of which I haven’t seen – but this film provides a successful example of combining the feminine and masculine voice in storytelling, something that the collaborative nature of film allows to happen. The film also taps into some intriguing philosophical territory, even while conveying an essentially melodramatic love story involving a mute young  woman (played by Sally Hawkins) and a primordial and monstrous amphibious creature (played by Doug Jones) reminiscent of the 1954 horror film, Creature from the Black Lagoon. Another, more recent, corollary being the film version of The Beauty and the Beast.

woman (played by Sally Hawkins) and a primordial and monstrous amphibious creature (played by Doug Jones) reminiscent of the 1954 horror film, Creature from the Black Lagoon. Another, more recent, corollary being the film version of The Beauty and the Beast.

Vanessa Taylor, who scripted the sci-fi film Divergent, honed her skills primarily as a television writer. The advantage of television writing is that it tends to force the writer to focus on character interaction and subtleties (when it’s good), and because of constraints of budget and time often tends to shy away from a dependence on special effects. It is the strength of the character’s interactions – coupled with a compelling story told in a unique way – that makes The Shape of Water so easy to watch.

The Shape of Water, sometimes billed as a fantasy/drama, also brings together a mélange of philosophical ideas in a very impressive way – ideas that may often be the brainchild of Mr. del Toro. While the film’s execution budget and scope are relatively modest in Hollywood terms ($19 million), the intellectual scope of the film extends quite further. Now, whether or not all of this philosophical ‘profundity’ is a result of my own personal meanderings over the past few years, or the intended result of the filmmakers, we’ll never know (unless I happen to meet them). Nevertheless, some readers might find the following reflections of value.

While many film professionals have, for a variety of reasons, recently flocked to television Read the rest of this entry »

Kenneth Lonergan is not the most prolific of directors, but when he makes a film it tends to have an impact. So it was with his 2000 classic, You Can Count On Me (reviewed by me here) as well as his recent dramatic effort, Manchester By The Sea.

On one level, Manchester is a story about time. Time overlaps, fuses, and conjoins in interesting ways, due to the non-linear way that Lonergan chose to tell his story. Not only does time overlap, but dialog does as well (overlapping dialog apparently being a favorite technique of Lonergan’s). The weaving of non-linear time and very focused, human, simple and in-the-moment scenes, along with overlaying classical music onto the scenes and transitions (extending Lesley Barber’s original score), gives the film a feeling of both the natural chaos of life and, ironically, of refinement. It is the tension between the two – the sublime and the tragically simple and human – that becomes the almost Zen-like framework through which Lonergan tells his story. This particular film probably could have been edited a dozen different ways, even though the outcome could have been essentially the same. As Lonergan said in an interview, the only way he could perceive the story being told was ‘all at once’.

This was absolutely by design; Manchester likely evolved into a final film in the editing room in a very real way, with substantial shifts and changes occurring at that stage.  Lonergan may have even shot the different aspects of the story without being 100 percent sure of how he would ultimately weave them together. He apparently went through several drafts in writing the script, throwing out many scenes, rewriting others, then starting the process again. The result can be at times confusing, but ultimately satisfying as Lonergan and team meld together various threads of a the tragic tale of handyman Lee Chandler (brilliantly played by Casey Affleck) as a pivotal error in his life caused him to lose literally everything, most importantly his two children. The film explores the consequences of that event.

Lonergan may have even shot the different aspects of the story without being 100 percent sure of how he would ultimately weave them together. He apparently went through several drafts in writing the script, throwing out many scenes, rewriting others, then starting the process again. The result can be at times confusing, but ultimately satisfying as Lonergan and team meld together various threads of a the tragic tale of handyman Lee Chandler (brilliantly played by Casey Affleck) as a pivotal error in his life caused him to lose literally everything, most importantly his two children. The film explores the consequences of that event.

While the story Mr. Lonergan tells is non-linear, the themes are timeless, as is the sea that surrounds the small fishing community where the events take place. The fundamental theme behind the story is one of redemption: how does one redeem oneself after a tragic mistake? Moreover, the film, it seems to me, focuses on the idea of how a person – a man – redeems himself in such a situation through what are essentially very simple actions.

Why would the story necessarily be different for a man than a woman? I will argue that this story is primarily about the responsibilities that men will often assume, mainly, fixing things in the way that the handyman Lee does. Moreover, the story evokes the necessity an ambiguity of accepting responsibility even where there is no clear ‘blame’ to be had. In the case of Lee, whose error was a simple and yet profound mistake, the question becomes one of context. The context of the mistake is that the character lives in a community that both created the framework of ‘stupid men doing stupid things’ to occur, and then makes it impossible for Lee to rejoin the community and accept their forgiveness – perhaps because there was a collective guilt associated with the deaths of Lee’s children because the tragedy took place as a direct result of a ‘boy’s night of fun’ that took place at Lee’s house, in the basement, where the children slept. His daughter’s deaths were, therefore, a communal responsibility.

That said, there is no real indication that, for the most part, the punishment for Lee’s error came from anywhere else than inside his own head. His wife Randi (played poignantly by Michelle Williams) did ultimately leave him, remarry and have another child. While Lee had a similar  opportunity for another relationship, he didn’t take it. His choice was not to forgive himself and not really to move on, at least not until the end, where he allows another human being into his life – his nephew who experiences his own personal tragedy.

opportunity for another relationship, he didn’t take it. His choice was not to forgive himself and not really to move on, at least not until the end, where he allows another human being into his life – his nephew who experiences his own personal tragedy.

Within the context of a fairly tolerant society (Lee was not accused of manslaughter) Lee slowly finds redemption through the de facto adoption of his brother’s son Patrick (played effectively by Lucas Hedges) after Patrick’s father’s death (Lee’s brother Joe, played stoically by Kyle Chandler) – even though here Lee is also unable to take on full responsibility for that task and does so in a very cautious, meandering way.

In a world defined by competence, Lee’s error was one of fundamental lapse in his generally competent self as evident in a stupid error. So it could be said of mankind in general, for the problems of the world are very much the problems created by men and their activities – with the efforts at ‘fixing’ things creating more problems than the problems themselves. That men have, for the most part, shaped the modern world, Manchester By The Sea suggests that perhaps is their special place to accept responsibility for making it right. The film also suggests this may be no easy task.

An alternative to a male-dominated world is never really explored, but we are left with a gaping hole in the film, the ‘need’ for someone to step in and take control when nobody really wants to. As with You Can Count On Me, there is an palpable absence in the film that can be, on a simplistic level, defined as God. Or perhaps it is, in this city of fisherman, the Jesus who never shows up, referring to the biblical Jesus who chose to recruit his disciples from among fisherman. On another level, this absence can be defined as the loss of love, or the ability to love one’s self, and to treat one’s self and others with respect.

The self-hatred evident with Lee would, in another era, be fodder for the redemptive role of religion. In this film, the cross is taken on by the individual, who must in a sense take on the role of the Christ in order to find redemption; there is, apparently, no other way for a modern man do so, or so it would seem. The film lacks any sense of a communal or individual spirituality, outside of an off-the-cuff (and humorous) allusion to Catholicism and the non-consequential appearance of a lone character randomly on the street (played in a cameo by Lonergan himself) who appears briefly (similar to Lonergan’s role as the priest in You Can Count On Me) to chide Lee about his lack of parenting skills. As with You Can Count On Me, such advice becomes almost comic relief.

Thus suffering, in Lonergan’s tale, is so deep and pervasive that the superficial balm of religion and/or of God can do little to provide comfort. Lee’s mistake, taken as a metaphor for the modern human, puts the only hope for salvation clearly in the hands of mankind itself, and perhaps even more specifically with men themselves, loath as they are nowadays to accept that there may be a sort of universal male attitude problem and inability to mature, particularly in the US, the country that has spread its influence quite effectively in the world, and where the fruits of that influence are a mixed bag, to say the least.

As for the story of Manchester By The Sea, the most moving moment is where Randi forgives Lee. It is in Randi’s forgiveness that the film ultimately speaks to reconciliation and the kind of catharsis that makes for great drama, although again Lee is unable to accept  Randi’s forgiveness as he can apparently not forgive himself.

Randi’s forgiveness as he can apparently not forgive himself.

At the end of the day, perhaps Manchester By The Sea seems to strike a chord with audiences because it portrays the perceived impossibility of our current world situation, where human beings have created their own hell through their own numerous errors in judgment, and have to somehow either fix it or sink with their own doomed ship. With the (male defined) world order clearly at risk, and the rise of scapegoating populism, it seems that the forgiveness displayed by Lee’s wife Randi is the only real hope for humanity.

Is this the ‘prescription’ given by Lonergan and Manchester By The Sea? Probably not, as I’m sure Mr. Lonergan would deny the film is in any way prescriptive in nature or perhaps not even recognize some of the comments that I’ve made about his film as being part of his intended result. But still, this is my takeaway and my advice from viewing Manchester By The Sea. For without forgiveness and love – and quietly accepting individual responsibility for our behavior without complaint or expectation of reward – without these qualities, there is only a never ending cycle of hatred and blame.

Don Thompson is a producer, filmmaker and playwright.

Warning: there are potential spoilers in this review.

We’re living in a transitional time, as evident in the upheaval of Presidential Politics in 2016. To a great extent, Hell or High Water, directed by Scottish director David Mackensie, reflects current trends that can trace themselves back most recently to the financial crisis of 2008, but even further to the Iraq War and further still to the dawn of Reaganomics in the early 80’s.

That the American Dream is not working out for everyone has always been the case, particularly for minorities. It seems, however, that this reality has reached an amplified level of desperation for non-minorities as well – specifically the working white poor – and thus is finding its way more actively into our films and our politics. Hell or High Water, with its desperate White Male protagonist Toby  Howard (played with rugged sensitivity by Chris Pine) who tries to outsmart a Banking system that seems intent on manipulating, cheating and throwing him under the proverbial bus (all legally) becomes the perfect anti-hero for today’s political and social realities. Toby, along with his self-destructive and yet self-sacrificing brother Tanner (played ferociously by Ben Foster), paint a pure picture of the moral morass the United States currently finds itself in.

Howard (played with rugged sensitivity by Chris Pine) who tries to outsmart a Banking system that seems intent on manipulating, cheating and throwing him under the proverbial bus (all legally) becomes the perfect anti-hero for today’s political and social realities. Toby, along with his self-destructive and yet self-sacrificing brother Tanner (played ferociously by Ben Foster), paint a pure picture of the moral morass the United States currently finds itself in.

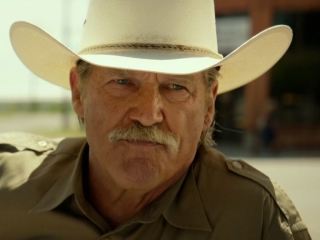

With this particular drama (and this film certainly rises to the level of drama), there is an attempt to explore not only conflict but also what the ancient Greeks would label stasis, or civil strife. This in turn evokes homeostasis – or the tendency to seek balance and stability. We find that balance here in the Texas Ranger Hamilton, played brilliantly by Jeff Bridges, as he attempts both to  find justice, remind us that we are a nation and community of laws, but in the end tries to empathize and understand what motivated Toby and his brother to rob a string of banks when apparently they (or so he thought) didn’t really need the money.

find justice, remind us that we are a nation and community of laws, but in the end tries to empathize and understand what motivated Toby and his brother to rob a string of banks when apparently they (or so he thought) didn’t really need the money.

We see in Ranger Hamilton an essentially fair-minded individual that gives us hope that stability and the rule of law will indeed prevail, even while the clever are allowed to profit. The clever being seen in both the Banking system and in Toby, who out-wits everyone, and in effect uses his own brother as fodder for the system, even as Toby sacrifices himself for his own (seemingly unappreciative) family.

His brother Tanner was the primordial warrior, needing essentially an enemy to fight in order to give him purpose. While unstated, his brother could have easily been a suicidal Iraq war veteran, although the writer (Black List winner Taylor Sheridan) sought not to expand his themes into that territory. One can only ponder the level of social commentary the film could have leveled on US society should Sheridan have taken that path.

Warriors often wreak damage on the innocent, and Tanner is no exception, made painfully evident to Ranger Hamilton when Tanner kills his partner, mixed Native American officer Ranger Alberto  Parker (played humbly by Gil Birmingham). Hamilton’s response becomes a tete-a-tete of revenge-based politics and war, with one side aiming to get revenge on the other in (what seems to many) an endless series of escalations. In the case of Tanner, the war fortunately ends with his death. In real life, such deaths are usually only the catalyst for more atrocities.

Parker (played humbly by Gil Birmingham). Hamilton’s response becomes a tete-a-tete of revenge-based politics and war, with one side aiming to get revenge on the other in (what seems to many) an endless series of escalations. In the case of Tanner, the war fortunately ends with his death. In real life, such deaths are usually only the catalyst for more atrocities.

That a Native American descendant would be Tanner’s central victim is no small matter, and also prescient, given the current situation with Native Americans and the Dakota Access pipeline. As Tanner exclaimed , he was a ‘The King of the Plains’ and felt he ‘was a Comanche’ (as told  at the Casino to a Native American customer whom threatened him). As such, Tanner too is a sacrificial warrior, with Hamilton (same last name as a US Founding Father!) doing the deed.

at the Casino to a Native American customer whom threatened him). As such, Tanner too is a sacrificial warrior, with Hamilton (same last name as a US Founding Father!) doing the deed.

It is no small coincidence for this film that among the primary ideas that Founding Father Alexander Hamilton (the guy on the ten dollar bill) sought to defend were private property and the need for Central Banking. It is this property and land, says Ranger Alberto in the best speech in the film, that the White Man is inevitably bound to lose to the Bankers, just as did the Native Americans did to their conquerors. It was apt then, that Ranger Hamilton be the Banker’s defender in this film.

That civilization uses its warriors as sacrificial lambs in order to maintain social stability is a repeated theme in war films, or films of warriors fighting for some sort of local or community justice, and seen in Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Interestingly, the The Magnificent Seven (based on the Seven Samurai) is also having a remake finding itself to the screen. These morally ambiguous stories, where the anti-heroes find themselves fighting  corruption for a seemingly unappreciative and/or apathetic society, seem to making their way back to theaters.

corruption for a seemingly unappreciative and/or apathetic society, seem to making their way back to theaters.

Another example of such a film (there are many) that comes to mind would be Michael Mann’s Thief, starring James Caan, where the thief desperately seeks normalcy, only to find that normalcy is an impossibility and a pipe dream. So it is for Toby’s brother Tanner who displays the same kind of self-destructive criminality as found in James Caan’s character in Thief.

As for Hell or High Water, this moral ambiguity is shown as the anti-hero brothers fight against a corrupt system because the brothers did in fact need the money, and the whole scheme was a way to turn the tables on the unfair (either corrupt or borderline corrupt) dealings of their local bank. Specifically, corruption in the guise of unfair reverse mortgage on their property, a property that Toby had been deeded to by his recently deceased mother and that Toby had found out was sitting on top of a lucrative oil patch.

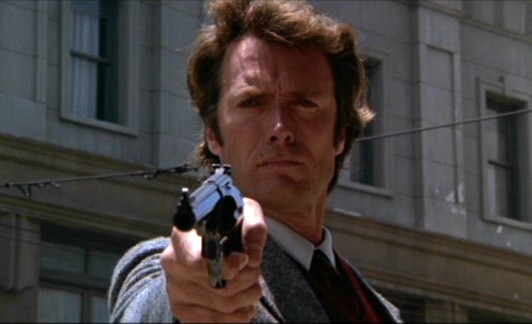

Hell or High Water also echoes back to a film franchise set during prior transitional political times. During the 70’s, just before Reagan, we had another series of films that one might call reactionary and emblematic of the politics of the time: the Dirty Harry series. Here the steely eyed San Francisco Cop (played iconically by Clint Eastwood) was going to lay the law down on the various threats to the White Man’s dominance of the United States: people of color, immigrants, and other assorted misfits and low lifes.

We can watch closely for a Dirty Harry re-do, with perhaps Donald Trump being the producer. It may have a limited audience, as Clint Eastwood recently dubbed the millennial generation ‘the Pussy Generation’.

On television, the 70’s had All In The Family (starring Carroll O’Connor), which made fun of conservative politics, but in an oblique way that allowed conservatives themselves to join in on the fun. Hell or High Water, with its social justice meme combined with essentially conservative, libertarian sentiments, uses a similar methodology – allowing the left and right to come together under the same entertainment roof.

Reactionary sensibilities aside, some potentially worthwhile and quintessentially American values are on display in Hell or High Water: those of property ownership, essential fairness and decency, having our children do better than us, financial independence, and rugged individualism are all on display in Hell or High Water.

The film, while on one level a tale of a revolutionary sticking it to the Man, is on the other hand a revelation of human folly. For at the end of the day, the oil that is pumped out of the ground on Toby’s land (now deeded to his Children) may lead to the death of his children’s hope for a future. In clinging to the illusions of past fossil-fuel driven prosperity, Toby may not allow his children the freedom to explore alternatives. This is perhaps the real, off-screen tragedy of Hell or High Water. But then, according to some, we can continue to pump that oil forever, and with no consequence.

But back to Dirty Harry. My sense is that demographics and the preferences of young people have so shifted since the times of Dirty Harry that we will not find a shift in politics to a modern-era Reagan – or certainly not under Donald Trump, who at least for now is trailing at the polls. In today’s  world, the desperate, angry White Male may have indeed found his match with immigrants, minorities, Soccer Moms and Hillary Clinton, and the resulting resolution may indeed need to be one of peaceful co-existence, or else all these angry White Men can only hope to go down in flames in a sort of nation-wide Waco, Texas confrontation (which occurred under Bill Clinton’s tenure). Let’s hope that’s not the case.

world, the desperate, angry White Male may have indeed found his match with immigrants, minorities, Soccer Moms and Hillary Clinton, and the resulting resolution may indeed need to be one of peaceful co-existence, or else all these angry White Men can only hope to go down in flames in a sort of nation-wide Waco, Texas confrontation (which occurred under Bill Clinton’s tenure). Let’s hope that’s not the case.

As an interesting side note, Hillary Clinton is the first woman mentioned in this essay.

Don Thompson is an essayist, producer and playwright.

(IndieWire) Summer is chugging along at the specialty box office.

Another acclaimed Sundance 2016 entry, Ira Sachs’ “Little Men” (Magnolia), showed a credible opening in New York and Los Angeles, as two of last week’s Park City 2016 premieres, “Indignation” (Roadside Attractions) and “Gleason” (Open Road), expanded this weekend to varying results.

Read more here...

Spoiler Alert: some story elements are revealed in this essay.

The word revenant means ‘one who has returned from the dead or from a long absence’. In the case of Alejandro Iñárritu’s film, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and written by Iñárritu with Mark Smith, it is DiCaprio’s true-to-history character of Hugh Glass that returns in order to take  revenge on the man who killed his son. So the story of The Revenant is one of nature and revenge, and nothing more.

revenge on the man who killed his son. So the story of The Revenant is one of nature and revenge, and nothing more.

That’s the simple part.

The not so simple part is actually analyzing this multi-layered film as a drama that transcends the revenge label to unveil a meditation on the relative nature of good and evil. As such The Revenant speaks to a modern audience who has in many ways lost the meaning of the word drama. The Revenant reintroduces film-goers to this recently problematic word as it explores the primal meaning of the human experience and attempts to strip bare civilized man (I say man because it is a film very much about men) to reveal what lies beneath.

Dramatists, artists and mystics, for the most part, seek to have us question the idea of absolute good and evil and hint at a common humanity that transcends our differences. The alternative is not really drama but more aptly labeled melodrama – what we are typically given in the name of drama.

This Trojan Horse agenda of the dramatist, artist and mystic – this request for us to question our simple and absolute morality – is at the heart of The Revenant. Yet, at the same time, the film portrays the tendency to seek absolutes in a relative world to be at the heart of the human experience, rising from the tendency to hate what brings us pain and to love what brings us pleasure. However, this film reveals, like any good drama will, that this primal human motive in no way shape or form delineates absolute good and evil, which is shown to be a chimera, changeable, relative, and completely dependent on your point of view.

To the Arikara tribe, the Americans are the enemy. To the Pawnee tribe, the French are the enemy. To the lone Pawnee, the American Hugh Glass is a friend. To Hugh Glass, Fitzgerald is an enemy. To Fitzgerald, Hugh Glass who betrayed his deal with him is the enemy. To the Europeans, the lone Pawnee is an enemy. To the Americans, the Indians in general are the enemy. To the daughter of the Arikara leader, the character of Glass is a hero. To the American Captain, the child-man Bridger is revealed as a hero. To the Grizzly Bear protecting her cubs and almost killing Hugh Glass, Glass himself is the enemy – and she is in many ways, in her primal protective mode, creating the entire dramatic context of the story.

Who then is the enemy, what then is this evil? Is it really mankind, imposing its will on pristine nature?

‘I leave the revenge to the Creator’, advises the lone Pawnee man to Glass, and Glass echoes this to Fitzgerald later in the story. The film, in conclusion, indicates it is better for human beings not to judge. This, indicates The Revenant, is the wiser path. That said, nature may not be without her own form of judgement.

As I watched The Revenant two other filmmakers came to my mind: Terrence Malick and P.T. Anderson, and more specifically Malick’s The Tree of Life and The New World and Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. Reviews written by myself for Tree of Life and There Will Be Blood can be found here and here.

Misha Petrick has also compared Andrei Tarkovsky‘s visual style to The Revenant in a split screen video here, and Iñárritu himself suggested that Tarkovsky has had a deep influence on him. I have not seen all of Tarkovsky’s films but found the visual comparison compelling. In interviews, Iñárritu also mentions Herzog, Kurosawa, and others as influences on The Revenant.

That said, Malick’s The Tree of Life and The New World also seem to me to be visual predecessors to The Revenant. Tree of Life and The New World, like Revenant, had a love affair between nature and the camera (in the case of The Revenant, an entirely new camera technology used to brilliant effect by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, who also shot The Tree of Life). Regardless, the result is art: the stillness of nature and its pristine framework forms the backdrop for men’s selfish machinations.

Nature, and particularly water, factor heavily in The Revenant as forces of both destruction and renewal. Many of the scenes of Revenant are directly or indirectly associated with streams or rivers. The dual nature of water, as both a destructive and redemptive force, are key to the evolution of the story. So too in Tree of Life did the river become a redemptive force as the young boy Jack seeks to wash his sins away with the nightgown scene. The water cleanses, renews, and washes away the old in favor of the new.

As in The Tree of Life, The Revenant shows that humankind’s social reality exists only within the context of a wider nature that is in many ways cold and without mercy. If mercy exists anywhere, The Revenant shows it to be in the small, individual human gesture, such as when Bridger offers food to the Indian woman or leaves the canteen with Glass with the labyrinth-like design etched on it. The key difference between The Tree of Life and The Revenant is that while the former posits that compassionate choice may exist outside of the individual human and arise out of nature itself, The Revenant more closely associates any potential compassion with the human realm; thus Tree of Life more directly supports the view that there is some sort of proto-rational, pre-human intelligence that leads us to choose compassion. For The Revenant, the creator God is reflected as a cold and judgmental nature, a nature that is essentially detached unless that detachment is altered by human will.

Tree of Life also suggests a detached universe reflected in the primordial expression of space and time that ultimately seeks a compassionate viewpoint when individual sentience (even animal sentience) arises. To Malick, as expressed in Tree of Life, this detachment could come in the way of an errant asteroid, also hinted at in The Revenant as the meteor flies overhead and lands somewhere in the distance. Both films posit that humanity lives within a certain folly in its obsession with the petty concerns of profit and loss, of pleasure and pain. That is, unless you’re a human being, in which case these petty human considerations are of life and death importance, and the meteor passing overhead is only a brief reminder of potential destruction and judgement from above, quickly forgotten as the next distraction takes hold of one’s consciousness and edges a person such as Fitzgerald in The Revenant to salvage the pelts, get the money, and pave one’s proverbial path to Texas.

It is in the mud that humanity must apparently sludge through in order to find redemption, and receive a glimpse of love and happiness.

What then is this love? Where shall it be found? Does love really present itself only when the proper choices are made, and when mankind turns away from hatred and realizes that nature (or God?) does not really judge us at all, that this too is a concept laid upon a pristine reality by the human mind?

These thoughts and questions meander through my own mind when reflecting back on The Revenant.

As for P.T. Anderson’s There Will Be Blood I am reminded that blood, like water, is a primal force as it is in The Revenant. Blood is, it seems, the sacrifice required for growth in this world. So is Hugh Glass ‘reborn’ from the blood and guts from the ‘womb’ of the Horse, just as much as he is almost killed by the bloody attack from the Bear. Nature both gives and takes life, and blood and violence is required. The ‘fall’ into the womb of the horse  (like a lower realm of hell in Dante’s Inferno) also rebirths Glass into the more hate-filled and obsessive purpose of revenge, whereas prior he had primarily been motivated by the desire to live and breath. It is only the mercy of women, along with restraint in judging Fitzgerald, that eventually leads Glass back to human love.

(like a lower realm of hell in Dante’s Inferno) also rebirths Glass into the more hate-filled and obsessive purpose of revenge, whereas prior he had primarily been motivated by the desire to live and breath. It is only the mercy of women, along with restraint in judging Fitzgerald, that eventually leads Glass back to human love.

For P.T. Anderson, violence is also justified, for it makes way for the new. In There Will Be Blood Anderson seems to promote the necessary bloodletting of the weak by the powerful, as the weak would have humanity forever acquiescing and accepting ‘the will of God/Nature’ and suffer needlessly as a result. This luddite thinking must be removed for progress to occur, or so goes the modern myth. Nature and others must be sacrificed, often violently, in the name of human progress, even if that progress ultimately destroys what it sought to merely dominate.

To D.D Lewis’s character Daniel Plainview, the protagonist of There Will Be Blood, those that seek a bloodless world are naïve and stripping mankind of the very force that gives it life and propels humanity forward. Thus Heaven or ‘spirit’, should they exist, are simply bloodless realities that the weak perennially and naively seek in order to escape what cannot be escaped from, the primal force of cold nature that doesn’t give a damn about them.

To the materialist, the ‘spiritual’ scenes in The Revenant of Glass vis-à-vis his wife are but mirages, hallucinations and mad meanderings. To the spiritual, they are visions of a greater, alternative world that transcends the perennial, bloody savagery of human life – no matter how hidden, sublimated, air brushed and ‘oh my goshed’ out of existence it is in our modern era – a savagery that buttresses the material world in its quest for food and shelter. The spiritual person replies that even if such realities are created by a hallucinatory mind, what makes them any less real than the hallucinations  of money and profit, of the shimmering hope of getting some land in Texas to settle down, as was the hope of the materialist Fitzgerald, a man who mocked God? His hope too, ultimately, was a chimera, a mirage, and a pipe dream. So too might be the very notion of human progress.

of money and profit, of the shimmering hope of getting some land in Texas to settle down, as was the hope of the materialist Fitzgerald, a man who mocked God? His hope too, ultimately, was a chimera, a mirage, and a pipe dream. So too might be the very notion of human progress.

Whether ‘real’ or ‘imaginary’ (with human beings the two often meld) it seems that human beings need a purpose.

It seems to me that human beings need a purpose in order to keep moving forward materially, artistically, or even spiritually. Without a purpose, whether that be revenge or love, heaven or hell, family or friends, profit or art, people cannot be adequately called human. Perhaps the problem with most of us is that we tend to let others define our purpose, rather than choose it for ourselves.

For the character of Hugh Glass in The Revenant, he very much chose his purpose by reacting to circumstances in a certain way.

For 20th Century Fox, an American Studio that put their stamp on an epic, big budget dramatic feature telling a human story that is not a super-hero movie or cartoonish blockbuster – and not gone to their ‘independent’ subsidiary to do so – perhaps that is another return from a long absence, another revenant of sorts. Time will tell.

**

Don Thompson is a producer, playwright and essayist.